In the fall of 2008, the 150-year-old financial institution Lehman Brothers spectacularly melted down. The liquefied remains then ignited, joining the worldwide conflagration that became the great recession that is now either over or not, depending on whom you talk to. In short order, a host of formerly rock-solid institutions showed cracks that ran all the way from their foundations to the aeries occupied by their greedy, ineffective senior management. Firms that once represented all that was trustworthy in our financial system teetered, then fell. Even insurance companies that were responsible for the welfare of others were revealed to be the oldest permanent floating craps game in New York.

The situation has had at least one positive aspect. Those who hate selfish, lunk-headed, avaricious, shallow, backstabbing business weasels have entered a halcyon era in which every day has brought juicy new revelations that prove, if any proof were needed, that business people are truly the buttheads we always thought they were. Gone are the days of the hagiographic profile in newspaper, book or magazine of the slick billionaire who made his bones pushing numbers around on a spreadsheet and cutting heads with a chainsaw.

Instead, a new growth industry has emerged to satisfy an acute craving for tales from the fiduciary crypt.

Today, every bookstore bulges with a variety of tomes dedicated to illuminating the dark underbelly of corporate capitalism and the dweebs who run it. Most of these books make for occasionally fun but depressing reading. Those who like being outraged for hundreds of pages can have a field day. But in the end, when the bodies have been swept away, a key question remains: What has been learned?

Vicky Ward’s “The Devil’s Casino” is an able new entrant into this crowded genre, and people who hate losers who are not their friends should enjoy it very much. It chronicles the sad and messy end of the House of Lehman in a relatively terse and fast-moving 270 pages, making it a mere social X-ray of a book by today’s standards of nonfiction heft, which often rivals the unsecured debt load of a failed bank. Ward carefully and skillfully tracks the last 25 or so years of the great, doomed enterprise, and her portrait of a business entity is often engaging, spicy and amusing. I particularly enjoyed the horror stories about those few, strategically challenged souls who had the temerity not to learn golf. Theirs was a demise that only outsiders to our fascist corporate golfing culture can appreciate. And the tick-tock of deals, fads, decisions and transactions that took place over a very long time can be exciting.

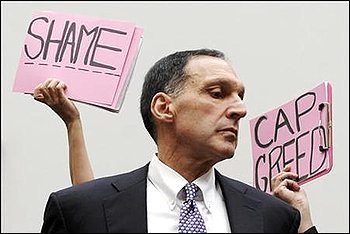

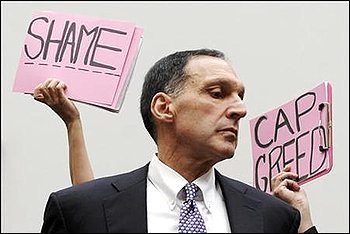

The book also does a fine job of sketching several outlandishly banal individuals who rose to prominence in the firm and ultimately were responsible, each in a different way, for its demise. In attempting to aggrandize and inject some drama into the characters in this saga, however, Ward may have achieved some unintended results. Her chief villain, naturally, has to be Richard Fuld, the chief executive, who is still hopping around on the media’s hotplate after the recent release of a 2,000-page investigative report on Lehman’s questionable behavior during his reign. Yet in spite of tales told out of school by a host of malicious Iagos who used to receive their bonuses from Fuld, and worshipped Fuld, and ate bonbons at the feet of Fuld, Fuld emerges, finally, as a pretty tragic and sympathetic creature, if something of a moral moron. What do you eventually feel about a guy who has to endure all this acrimony from mostly unnamed sources or those with whom he had a business beef? Me, I start to feel sorry for him.

You also have to feel tremendous empathy for the families of these driven Lehmanites, who essentially caught a full dose of Stockholm syndrome while trapped in this overheated casino. Wives of established moguls routinely snubbed those of guys who were suddenly being strangled by the internal grapevine. One beleaguered business spouse was forced to go through labor by herself because her husband had a conference call that just couldn’t be missed, you know. “But I wouldn’t get mad at him,” she told Ward: “If you made a personal choice that hurt Lehman, it was over for you.”

It’s tempting to conclude that what we’re dealing with here is not a cadre of crafty, evil wizards, but simply a bunch of petty, vicious schmucks. Take the genuinely unattractive figure of Joe Gregory, whose nickname was Uncle Joe, after Stalin. Certainly, the way Gregory rose to the top provides a cautionary tale for those who think corporate life is a meritocracy. But who really thinks that anymore? And what does all this Sturm und Drang have to do with the systemic attitudes toward risk and gain that brought the firm down? Very little, really. For it turns out that Ward’s heroes were as guilty as her villains.

This is particularly true of the book’s ostensible D’Artagnan, Chris Pettit, whom Ward, straining mightily, paints as a mix of George S. Patton and Vince Lombardi. “Pettit’s ethos so infused and inspired [the Lehman team] that a corporate video about the firm’s history referred to the period before his arrival as a chaotic, unenlightened time: ‘B.C. — Before Chris.’ ” The only problem with this analysis is that Pettit turns out to be a highly recognizable type to anybody who has worked with a former military man morphed into a corporate officer: yelling, cursing and in the end fighting for his enormous severance package just as hard as Ward’s supposed miscreants, and eventually drinking and screwing his way to his own destruction.

In fact, the frightening thing about “The Devil’s Casino” is, for all the author’s valiant efforts to elevate the tale, how ordinary it all seems, each act providing sad examples of what happens to regular people when they work too hard, drink too much and make too much money in a crazy ecosystem that rewards so many dubious practices.

And then, finally, there are the limitations of the corporate autopsy discipline itself. While Ward had access to much precious written material from corporate sources, she still uses tons of unattributed quotes from people who were in the know, got shafted and now have something to say about it. Dramatic interludes fraught with ostensible meaning are followed by parenthetical notes informing the reader that the principal actor in the anecdote completely denies its veracity. And, of course, those who cooperated with the exercise do better in the retelling of events than those who did not.

But who cares if a few fish in this barrel are wrongly shot? It’s all in a good cause. We’ve learned the lessons taught by Ward and her many contemporaries. Gone are the days when irrational, avaricious, petty people take inordinate risks for evanescent gains. Saner minds have prevailed. New regulations are in place to control the natural order of things when there is so much lucre around. Business as we know it has changed forever.

And if it hasn’t? If the rules are still pretty much the same as they were for Fuld and his gang, and show no genuine signs of improving? Why do we have the right to feel any better about ourselves than we do about those idiots?

Stanley Bing is the pseudonym of an officer in a Fortune 500 company. He writes a column under that byline for Fortune magazine.