Buyer’s Remorse: Inside the Art World’s Billion-Dollar Rivalry

The rumor sped through the crowd like a missile. It was December, and the art world had gathered under the sun for Art Basel Miami Beach, the industry’s last big celebration of 2014. On Tuesday there was the opening reception; while dealers were putting the finishing touches on their booths at the Miami Beach Convention Center, the Design Miami fair was kicking off in a tent next door, and that was where many of the week’s guests were (the organizers anticipated 73,000), chattering about the night’s dinner options, when the news landed.

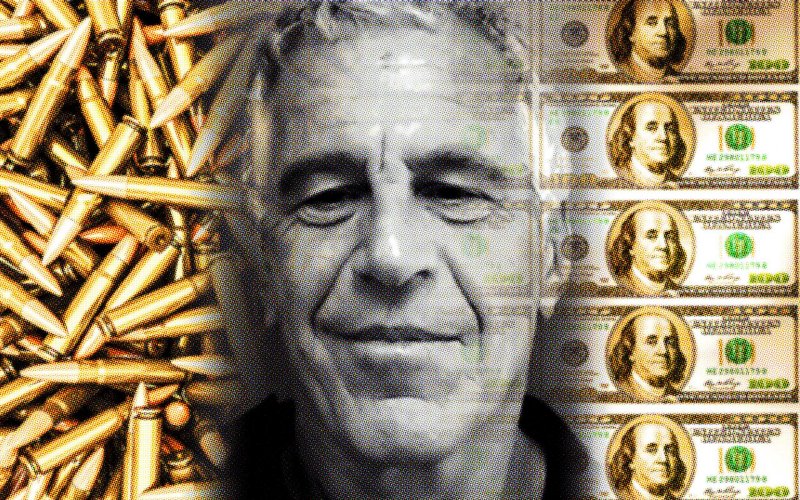

Stephen P. Murphy, the fast-talking 60-year-old CEO of Christie’s, who was unexpectedly anointed in 2010—the first American to head the 250-year-old British auction house—had stepped down. Suddenly. He was scheduled to sit on a panel on luxury goods in Miami the next day, but apparently that was no longer happening. The story going around was that he had been fired by Patricia Barbizet, the auction house’s quick-witted 59-year-old chairwoman. Murphy’s tenure at Christie’s had been marked by massive sales of postwar and contemporary art, and supposedly his contract had just been renewed. Nevertheless, later that day a press release thanking Murphy for “his vision, leadership and commitment to Christie’s” went out, and that was that. Officially, no further word was uttered on the subject. Barbizet would take over as CEO, the auctioneer Jussi Pyllkkänen would become global president, and Stephen Brooks, known internally as “the money guy,” would become global COO.

Dom Emmert / AFP / Getty Images

As for Murphy, he was not there to defend himself against the deluge of allegations roiling in the South Florida heat. had some personal transgression been unearthed? Or was the reason the headline-grabbing deals, the red-letter names, and the steadily ascending earnings under Murphy’s leadership, which, in what appears to have been the worst-kept secret in the art world, somehow resulted in less than robust profits for the auction house?

Was something amiss beneath the glossy surface? No one needed reminding that the last time a head of Christie’s abruptly resigned (Christopher Davidge, in 2000), it was because Christie’s and its eternal adversary, Sotheby’s, were about to be laid low in a vast price-fixing investigation that would land former Sotheby’s owner Alfred Taubman in jail.

Months later people are still asking, and not out of mere prurience, what happened to Steven Murphy? And what does his fate—and that of Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht, who had announced his resignation just two weeks earlier—mean for the world’s two biggest auction houses?

Steven Murphy arrived at Christie’s during an era of seismic change in the auction of Willem de Kooning. The auction houses knew in whose homes most of these treasures lay, having painstakingly cultivated relationships with well-to-do families and their executors for centuries. (Christie’s was founded in 1766; Sotheby’s in 1744.) Selling art (and jewelry and furniture and watches and wine—the entire range of an estate’s luxury possessions) is not a short-term business. Guy Jennings, the former deputy chairman of Impressionist and Modern Paintings at Christie’s, explained it thus to a slightly different times. Put one person under each tree to catch the fruit when it drops. Shaking the tree will not bring it down any sooner. And rushing around from tree to tree in a mad frenzy when you think the fruit is about to ripen is not the most sensible way of doing it.” Jennings added, “Murphy appeared to think otherwise.”

To be fair, Murphy wasn’t hired to maintain the status quo. He was hired because François Pinault, the 78-year-old luxury goods magnate who owns Christie’s, agreed with both Barbizet and the company’s then-CEO, 54-year-old Brit Edward Dolman, that a “fresh pair of eyes” might be beneficial in a fast-changing business.

Dolman, a former rugby player with sandy hair and a gentle voice, had served Pinault well as CEO for 11 years. The two were close, even though they made an unlikely couple. Dolman has only “dinner-ordering French”; Pinault is not comfortable speaking English. Dolman’s frame is so big he looks awkward in an office chair; Pinault is slight. Dolman is classically British: dry, funny, understated, and seemingly (and only seemingly) half-asleep.

Pinault is openly alert, with a forensic French style. But it was Dolman who, after working his way up from porter to expert, then manager, steered the house through the upheaval of the price-fixing investigation. It was Dolman, furthermore, who quickly returned the house to profitability after the recession in 2001, and again after a dip in 2008.

In an interview in New York in January, Dolman explained that he, Pinault, Barbizet, and Pinault’s “finance team” would meet at least once every quarter to measure, among other things, their results against Sotheby’s. “The French are very scientific,” Dolman said. “I actually thought Sotheby’s [a public company] had an advantage because they couldn’t see our results, whereas I worked for someone who measured us directly with Sotheby’s. Anyone who thinks that Mr. Pinault somehow was so rich that he had no interest in whether Christie’s performed well is deluded. Mr. Pinault is a successful businessman because he wants to run businesses profitably, and that’s certainly what he expected of Christie’s.”

By 2010, Dolman recognized that new challenges faced the industry. A host of rich buyers had emerged in Russia, China, and Qatar. The new buyers wanted exclusively contemporary art, of which there is almost an infinite supply (as opposed to, say, Impressionism), and they didn’t want to wait for seasonal auctions to buy and sell it. As a result, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s increasingly found themselves in the business of private sales—transactions in which the auction house links buyers and consignors who do not want a bidding contest—which had several tricky consequences. One was that the in-house experts, who traditionally had been compensated for deals on a relatively flat basis, could now jostle for large commissions, which created friction. “Usually a sale doesn’t come about just because of one person,” Dolman says.

An even bigger problem, however, was the so-called “guarantees” both Sotheby’s and Christie’s were offering to discourage private sales. With the guarantees—promises to sell items for a minimum price—the houses enabled sophisticated collectors and dealers to exploit the companies’ desperation to create headlines and outgun each other in the public arena. Quickly the demand for guarantees became unaffordable, forcing a dependence on third parties (often top private dealers, sometimes financiers) and leading to industry scuttlebutt about how top collectors had found new ways to enrich themselves and screw the auction houses in the process.

For example, there were tales of friends bidding up each other’s works, and of sellers bidding on their own guaranteed property, all of which was legal as long as the guarantees were disclosed either in tiny legal print in the back of a catalog or in the rushed words of an auctioneer before a sale started. At both houses the staff knew they needed to stay one step ahead of their clients to ensure that they were not fleeced. “You have to be very conscious of the market manipulation that goes on in sales,”Dolman says. It was a new world of sophisticated and abstruse dealmaking, as confusing—perhaps intentionally so—as the world of credit default swaps.

With this in mind, in 2010 Dolman and Barbizet reached out to Steven Murphy. Murphy’s career had been a bit odd: From 1991 to 1998 he helmed the record label EMI. Then he moved into publishing; from 2002 to 2009 he was first president, then CEO, of Rodale Inc., a publisher of wellness magazines and books. (Like several of Pinault’s businesses, it’s a family-owned enterprise.) In 2003 Murphy greatly enhanced Rodale’s bottom line when he released the best-seller The South Beach Diet, which reportedly raked in $100 million. He also published Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. People who worked for him by and large loved him. Josh Deutsch, chairman and CEO of Downtown Records, worked with Murphy at EMI and says he was “the best boss I ever had.”

Dolman thought that, given this history, Murphy would understand the challenge of managing brilliant creative people—in this case the in-house experts, for whom “bagging a public deal, selling a painting in public, and the accompanying cocktail party chatter” are “life and death,” but who are not paid to consider whether a deal’s terms increase or decrease the house’s profits. As Dolman saw it, the CEO’s job was to balance what a 2009 Harvard Business Review article called “irrational” decision making (“decisions made for ego, for public consumption,” as Dolman phrased it) against “rational” decisions that quietly and boringly make money.

That Murphy, an outsider, was unversed in the weblike intricacies connecting contemporary art buyers and dealers (for example,the Mugrabi family is friendly with publisher Peter Brant; between them they control most of the world’s Basquiat and Warhol market) did not overly concern his supporters, not least because when Murphy was hired, Dolman, who was being promoted to chairman,was there to hold his hand. “Murphy was hired to turn us into a great big global brand,” says a very senior executive at Christie’s who always liked Murphy. “He understood media, the internet, PR. He was an aggressive business-getter. But Ed Dolman was the one with decades of experience in the business. Ed was the art world insider. The idea was they’d be a dream team.”

The dream ended quickly. In June 2011, nine months after Murphy’s arrival, Dolman left Christie’s to become director of the Qatar Museums Authority. He now says he quickly found he didn’t like being chairman after all. “I preferred being CEO,” he says. He also wanted to become a shareholder. “One of Mr. Pinault’s great strengths is that he’s very sure about these things, and we had no equity plan at Christie’s,” Dolman says diplomatically. Qatar was “a great opportunity.”

Some of Dolman’s former colleagues are more blunt, saying that, under Murphy, Dolman saw irrational business decisions at Christie’s that he didn’t feel were sustainable. Guy Jennings, the Impressionist expert who would leave Christie’s in 2014 after clashing with Murphy, says, “He wanted to maximize revenue now, now, now, or yesterday if at all possible. I asked him what he was doing for our children, but he wasn’t interested in the long term.”

Murphy embraced the modern way of doing business. He was unafraid of issuing vast guarantees; in fact, he was unafraid period. In 2011 he added Loic Gouzer, 34, to the contemporary art department. A good-looking Breton, Gouzer until 2009 had been at Sotheby’s, where he was seen as a loose cannon, but he was aggressive and had a roster of hip young clients, including neophyte collector Leonardo DiCaprio. Murphy felt Gouzer’s presence was good PR. In May 2014 Gouzer held his own contemporary art sale, called “If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday” (the title was inspired by a Richard Prince painting), which was widely written up—not because it made spectacular profits (it was reported to be a heavily guaranteed sale) but because of its slick packaging, which included a YouTube video of skateboarder Chris Martin maneuvering through Christie’s back offices to the music of Awolnation.

In all, Murphy spent a reported $50 million beefing up Christie’s marketing while modernizing the venerable firm with online auctions and its first public sale in Shanghai. In interview after interview, on television and in print, he also became the public face of Christie’s, and he seemed to revel in his iconoclastic reputation. He spoke often about “democratizing the art business,” which Dolman now calls “sound bite bullshit. How do you democratize a $20 million Warhol?” Yet it all seemed to be working. Starting in 2012, Christie’s contemporary art auctions started to roar.

In the summer of 2013, I met with Steven Murphy. It was a radiant day in London—one of those days the British, strangers to air conditioning, find too hot. Full disclosure: He was interviewing me, not the other way around, for a job, that of “chief content officer,” which he subsequently gave to someone else. Truthfully, I didn’t mind this outcome, not because the job wasn’t worth doing but because to do it well you’d need to be near Murphy, who was based in London. (He and his wife, parenting guru Ann Pleshette Murphy, had relocated there from New York.)

Murphy was dressed in a beige summer suit, and he had the spirit of a playful young Labrador about him. He talked fast and jotted down ideas. Like many Americans new to London he name-dropped a bit, but not annoyingly. He was passionate about taking Christie’s into the publishing business, both digital and print, and the time we spent bouncing ideas around was pleasurable. The meeting concluded with the two of us, both English literature majors, comparing favorite books and him promising to tell me in detail what happened to him during his “gap year,” the time he had spent after leaving Rodale for various parts of the Third World.

I left thinking he’d be a fun person to work with, but also that the job would be all-consuming, rather like a marriage. Barry Diller, the chairman of IAC, famously said a business leader must keep chucking ideas at the wall to see which ones stick. Clearly, this was Murphy’s approach. But I wasn’t sure of the stickiness of his brainwaves. “Maybe this will turn out to be a hugely important conversation,” he said during our meeting, whichI felt was an odd thing to articulate aloud.

I wondered how this effervescent fantasist got on with the taciturn and deadly practical Pinault, who had phoned him in the middle of our interview. “We get on fine,” Murphy had told me, but I was not convinced. I have spent time with Pinault in New York, Paris, and Venice, and I’ve seen the Frenchman’s blue eyes light up, but usually this happens when he sees a piece of modern art, its creator, or a luxury deal. Steven Murphy was none of these.

Hindsight makes it clear that Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht reacted all wrong to what he perceived as Murphy’s success. Like Edward Dolman at Christie’s, Ruprecht was a lifer who had ascended from the bottom of the auction house (in his case, a summer job as a typist). Like Dolman, Ruprecht, 58, was a former expert (in rugs). Both men had assumed the stewardship of their respective institutions in 2000, at the start of the price-fixing investigation. Both were seen as having risen to the challenges of corporate management.

But in December 2012, after he had been president and CEO for 12 years, Ruprecht was elected chairman of the Sotheby’s board. Many close to the business talked of being shocked. “Bill has never been a big outside presence,” says someone who has worked with Ruprecht for many years. “It was the ideal moment to get a complement to him, a fantastic, high-profile person. When that happened instead, I thought, They’re in for a management change one of these days.”

One person who took careful note was Daniel S. Loeb, owner of the hedge fund Third Point. Loeb has a record of buying stock in public companies he sees as needing a shake-up, then putting himself on the board, raising the share price, and cashing out. His most famous turnaround has been Yahoo, whose CEO he forced out in favor of current head Marissa Mayer. (A year later he sold his initial stake in Yahoo at a profit of 129 percent.) Loeb, 53, is a New Yorker and a contemporary art collector. He owns works by Warhol, Basquiat, Cindy Sherman, and Richard Prince. He is also friends with Tobias Meyer, then Sotheby’s principal auctioneer.

In the summer of 2013 Third Point bought 5.7 percent of Sotheby’s shares, which many saw as indicating that Loeb intended to supplant Ruprecht and replace him with Meyer. The commanding, German-born Meyer ran Sotheby’s contemporary art department—the division getting walloped by Christie’s booming sales of balloon dogs and squeegee paintings—and the frustration in the department was thought to be all-consuming.

“To the outside world the headlines of’Christie’s blows everybody away’—it was completely ridiculous,” says a well-placed Sotheby’s insider (not Meyer). “Christie’s was giving away most of their earnings for a big flash of market share and huge numbers. They don’t care what the net results are.”

The auction house’s secret strategy may have been exposed last year by megacollector Peter Brant, who admitted to the New York Times that when he sold a balloon dog to Christie’s in 2013, the auction house not only waived its standard commission fee (which for the $58.4 million piece could have been a whopping $5 million) but also gave him a large share of the fee it normally would have collected from the buyer. In other words, Christie’s was prepared to sacrifice much of its profit for the gloss and glory of coming in first.

“They do not disclose the deal structure, so you don’t know how much has been given back,” the Sotheby’s insider says. If Christie’s loses money on deals, no one outside the company knows; there are no shareholders and no publicly issued profit-and-loss statements.

When Loeb began accumulating shares, some assumed he intended to empower his friend Meyer to fight back using similar tactics. In fact, Meyer left Sotheby’s shortly afterward, and when, in October 2013, Loeb did finally call for Ruprecht’s resignation, he castigated Sotheby’s for trying to blame its problems on “predatory behavior by Christie’s.” It was Sotheby’s, Loeb wrote in an open letter, that had “most aggressively competed on margin, often by rebating all of the seller’s commission and, in certain instances, much of the buyer’s premium to consignors of contested works.” By then Third Point had amassed 9.3 percent of Sotheby’s stock, becoming its largest shareholder. Loeb also criticized Ruprecht for receiving a lavish salary of $6 million per year, including such perks as a driver and country club memberships, while his company suffered “chronically weak operating margins and deteriorating competitive position.” Sotheby’s, he famously added, was like “an old masterpiece in desperate need of restoration.”

Ruprecht reacted quickly, initiating a poison pill that stopped Loeb from amassing more shares. And something that arguably should have been done in 2012, when the board chairmanship was open, finally happened: Domenico De Sole, the renowned co-founder of Tom Ford International who transformed Gucci in the late 1990s, joined the Sotheby’s board as lead director. De Sole, 70, a Harvard-educated lawyer, met with Loeb and made it his business to stay friendly with him throughout what would become an all-out war. In February 2014 Loeb asked for board seats for himself and two others: Harry J. Wilson, a former U.S.Treasury official, and Olivier Reza, the head of Alexandre Reza, a Paris-based luxury jeweler. Ruprecht responded by putting up his own three candidates, the so-called “Sotheby’s slate.”

In late April the two sides headed to court in Delaware, and over a weekend in May—just before the house’s spring auction of con-temporary art, which set individual records for sales by Julian Schnabel, Keith Haring, and Matthew Barney—a compromise was hammered out, thanks to back channel diplomacy by De Sole. Loeb, Reza, and Wilson would get their seats (as would the Sotheby’s slate), and Loeb would get $10 million to pay his legal expenses.

Officially, order was restored. Loeb was often seen in the Sotheby’s headquarters on the Upper East Side. So was De Sole, who joked to me that he joined the board because he had thought it would be “interesting—but I hadn’t quite realized how interesting. “Loeb also complained to friends that Sotheby’s was more time-consuming than any of his other investments. He had gotten himself onto the board, but now what? “How do you think you can fix this, Dan?” he was asked by people on the Sotheby’s staff. If he had answers, he wasn’t revealing them. Since Loeb joined the board, Sotheby’s stock price has spiked several times, but overall it has been stable.

Still, on November 20 it was leaked that William Ruprecht was stepping down. The announcement came 10 days after a triumphant auction at Sotheby’s of masterworks belonging to Bunny Mellon that fetched $159 million, exceeding estimates, but only eight days after Christie’s trounced its rival yet again in the latest contemporary sales, $853 million to $344 million.

Sotheby’s board had reached a “mutual decision,” the press release would read. Ruprecht would receive severance totaling $6 million, and he’d stay on until June 30 while a search committee led by De Sole looked for a successor. Prominent headhunting firm Spencer Stuart (which had brought Marissa Mayer to Yahoo) was engaged; there has been talk of a very long short list that inevitably included Tobias Meyer; Amy Cappellazzo, another friend of Loeb’s and the former international chairman of Postwar and Contemporary Art at Christie’s; LACMA head Michael Govan; and MoMA chief Glenn Lowry.

If ever a time had come for Steven Murphy to celebrate, this was it. Sotheby’s was way behind in contemporary sales, its management in disarray. Indeed, at dinner parties with his close friend Lady Fiona Carnarvon (owner, with her husband George Herbert, 8th Earl of Carnarvon, of Highclere Castle, the setting of Downton Abbey), Murphy seemed relaxed, confident. According to friends, he and his wife were trying to figure out where to stable their horse and whether or not to rent a weekend cottage on the Highclere estate. And so he was caught utterly off guard when he was summoned to the now famous meeting on December 2. “He simply had no idea,” his wife told friends.

One person not surprised was Edward Dolman, who had returned from Qatar the previous summer and assumed the stewardship of Phillips, the so-called “third auction house.” “I think,” he mused, “what you are seeing is the rational side of the business taking over from the irrational. Pinault makes decisions quickly. He doesn’t have to answer to a board,” Dolman adds. “When he makes up his mind, he executes.” Others speculated that Ruprecht’s departure, since it left Sotheby’s in a bad spot, offered the Frenchman an opportunity to let go of Murphy. “He’s concerned a downturn is coming in the luxury goods sector,” says someone close to him. (Ten days later Pinault’s son François-Henri fired both the CEO and the creative director at Gucci.)

While the relative timing is striking, the changes atop the auction houses are not comparable in that Christie’s, unlike Sotheby’s, is perceived as extremely stable. Patricia Barbizet is widely considered capable, as are Pylkkänen and Brooks. “It may be the business has gotten too tricky for just one person to run it,” one senior executive at Christie’s says. Barbizet is said to have scheduled four meetings with Pylkkänen in the first 10 days of January. Sotheby’s, meanwhile, has witnessed little easing off in dealmaking on the part of its competitors. “If [Murphy’s firing] was supposed to be some sort of smoke signal—we’re going to make more sensible, profitable deals—well, we’re not seeing that,” says a Sotheby’s insider.

Whoever comes in at Sotheby’s, a complete remodeling of the business is in order, according to Dolman. “Sotheby’s and Christie’s are so big they’ve become institutions,” he says, adding that in the current era, when contemporary art “takes up two-thirds of the business,” it may not make sense to have huge overhead elsewhere. Phillips, of course, has the advantage of being lighter and nimbler than its counterparts. “I like the idea of a small, high-end, high-quality business, focusing on particular areas of the market without trying to be all things to all men,” Dolman says. A flow of applicants from both houses came to his door during the current uncertainty.

As for Steven Murphy, he appeared to recover quietly. He sent e-mails to old friends wishing them a Merry Christmas. He still visited Fiona Carnarvon on weekends. He held a farewell party for Christie’s staff at his Chelsea townhouse, but there was no sign he was leaving London for New York.

“It was unfortunate he was let go the way he was,” says a former Christie’s colleague. “I don’t know why it was necessary. I liked Steven.”