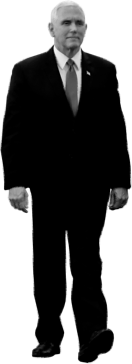

Pence has always relied unusually heavily on his staffers, according to five people who have worked with him. One confessed to being “surprised” by his malleability. A consultant who knows Pence well explained that while he is ideologically unshakeable, he is often unsure about operational matters. “If you bump into him at an airport and tell him he needs better yard signage, he will immediately assume you are right,” said the consultant, who has done pretty much just that. [1]Before Ayers’ arrival, Pence could not quite bring himself to tell Josh Pitcock, his well-liked aide of 12 years, that he was going to be replaced. Instead Pitcock, who was planning to depart at some point anyway, found himself having endless, confusing calls with Ayers about the newcomer’s role. Eventually, Pitcock suggested: “Why don’t you just have my job?”

In the early months of Trump’s presidency, according to a former senior White House official, Pence had been “acting like a staffer, wandering in and out of the Oval Office with nothing to do.” Ayers swiftly inserted himself into meetings at which Pence had not been included and carefully guarded access to his boss. Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council and an old Pence friend, told me that for a while he couldn’t even get his calls returned. Ayers was also close with the right people. He had ingratiated himself with Jared Kushner and the younger Trumps while volunteering as an adviser for the campaign and later as a well-regarded member of the transition team. (He and the Trump sons share an enthusiasm for hunting.) After arriving in the White House, Ayers started flattering Trump’s chief of staff, John Kelly, relentlessly. (A regular West Wing visitor told me that Kelly “completely has his number.”) [2]Another example of a canny Ayers attempt to win support for himself within the White House: In October, Ayers exhorted a gathering of RNC donors at the St. Regis hotel in Washington D.C. to purge any Republican lawmakers who failed to vote for the MAGA agenda. Somehow, a recording of the speech found its way to Politico. Trump’s inner circle reportedly approved.

Perhaps most useful of all is Ayers’ knack for staying on the right side of the president. During the 2016 GOP primary, Ayers served as chief strategist on Pence’s gubernatorial reelection campaign in Indiana. Pence remained strategically supportive of nearly all the final presidential candidates. He eventually endorsed Ted Cruz in a video, but was so flattering of Trump that Trump would (not incorrectly) call it “more of an endorsement for me.” People on the Cruz campaign detected the hand of Ayers. “Nick is really good at threading a needle,” one person close to Cruz explained.

These days, Pence is almost deferential around his chief of staff, two sources told me. “The more Nick is right, the more the vice president is empowering him,” said one. And the 2018 midterms will see Ayers’ power expand significantly. It is Pence, not Trump, who will anchor the GOP’s urgent effort to avoid massive losses in Congress. By the end of April, Pence will have appeared at more than 30 campaign events this year, with Ayers masterminding the details. Ayers is also one of the chief arbiters of which candidates receive money from Pence’s leadership PAC, the Great America Committee.

Even Ayers’ many detractors concede that he’s very good at his job. A number of Republicans believe he has salvaged Pence’s chances of succeeding Trump as president—which is very far from where he was nine months ago. The person close to Cruz said that Cruz would not run against Pence unless he is implicated in a serious finding by Mueller. “Ayers is critical to helping Pence (and by extension the GOP),” this person wrote me. On the one hand, he explained, Ayers “is carefully crafting strategies to show Trump [Pence] is loyal.” On the other hand, he went on, Ayers “is insulating Pence from Trump’s radioactive decisions. No easy task. Few can do it consistently. Ayers is a master at it.”

In person, Ayers is known to be exhaustingly charming. He has a panache you don’t normally encounter in D.C. Floppy blond hair, wide smile, swift stride, expensive suit. His greatest weapon is a Southern drawl that makes you feel as if everything is happening in slow motion. “If you talk slow, people think you think slow,” said Mark Meadows, the Republican congressman and chair of the House Freedom Caucus. “[Ayers] thinks four times as fast as he talks.”

Despite his age, Ayers is solicitous in the manner of a courtly older gentleman. Sometimes, he will ask permission from reporters to remove his coat or tie with an elaborate politeness. He is given to grandiloquent declarations of integrity. “One thing I am not, is I am not a liar,” was an example recalled by a Republican consultant who has spoken with him often. “I am always truthful. People can call me a lot of things, but one thing I am is a truthful person.” This “Southern Baptist preacher schtick” is the sort of thing GOP donors “swoon over,” the consultant told me, but it doesn’t always go over so well with Ayers’ peers. “Almost every operative that comes across Nick just absolutely cannot stand the guy,” the consultant added. Still, while Ayers’ affect may be cloying, it does place his principal guiding motive—himself—disarmingly in plain sight at all times.

It is a central tenet of politics that you can have money or power, but not the two at the same time. Ayers is a rare exception. He is not shy about showing his wealth—issuing gracious invitations to hunting parties on his estate on Georgia’s Flint River; sending Christmas cards that are fatter than most and wrapped in a bow. He has occasionally been known to lease a private jet—unusual among a crowd of strategists-for-hire who are accustomed to Marriotts and economy class.

When he joined the administration, Ayers’ White House financial disclosure attached some hard numbers to his high-roller image. After less than seven years of working as a political consultant and a partner in a media buying firm, Ayers reported a personal net worth between $12 million and just over $54 million. (For context, one leading strategist told me that a top-level consultant could expect to make $1 million in an election year and about a third of that in the off year.) And his business arrangements can be difficult to track. In the 2016 election cycle, Ayers spearheaded the Missouri gubernatorial campaign for Eric Greitens, who is now under indictment for invasion of privacy. In addition to the consulting fee of $220,000 paid to Ayers’ firm, he was paid over what appears to be a very similar time period by at least two different entities involved in the race.

Astonishingly, when Ayers entered the White House, he didn’t immediately sell his lucrative business, C5 Creative Consulting, as previous administrations would have required. He also obtained a broad waiver permitting him to talk to former clients. His ownership of C5 turned his White House job into a minefield of possible conflicts of interest. As chief of staff to the vice president, Ayers’ duties can include advising Pence on which candidates to support—decisions that can have a huge influence on fundraising and, hence, political advertising. In addition, in his private work for the Pence PAC, he is in a position to steer donor dollars into races where the company could potentially benefit. “That’s staggering,” one seasoned Republican operative told me.

In an environment where ethical scandals are spilling into public view on a near-daily basis, each seemingly more flagrant than the last, no one paid much attention to Nick Ayers’ consulting firm. Ayers himself declined to speak on the record and did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this article. After multiple attempts to clarify the status of Ayers’ business, Pence’s office sent a statement just as this story was going to press to say that his next financial disclosure in May “will reflect” the sale of his company. The White House provided no proof that the sale had occurred.

Waiting for so long into his White House tenure to address the issues posed by his ownership of C5 (and seemingly only under pressure) was a characteristic move from Ayers—and one strikingly at odds with the plain-spoken virtue that the vice president seeks to project. But, as is clear to those who have followed Ayers’ rapid ascent to the top of his profession, he has made an art form of skillfully navigating the gray areas in electoral politics. And in the process, he has demonstrated that the real danger in our porous, post-Citizens United campaign-finance regime isn’t always what’s illegal, but what’s been made possible.

Two years later, Ayers was running Perdue’s reelection campaign. The 22-year-old gained a reputation for being a shameless self-promoter, a recurring accusation he has never done much to dispel. A post on the Georgia political blog Peach Pundit observed that people were “so focused on hoping Nick Ayers screws up the Governor’s race and gets egg on his face that they’ve forgotten they should be focused on getting the Governor re-elected and worry about Nick later.”

Less than two weeks before the election, Ayers did get egg on his face. One night, on his way back to campaign headquarters, he was arrested for driving under the influence. Refusing a breathalyzer test, he admitted to imbibing a Jack Daniels and Diet Coke. (All counts were dropped except one for reckless driving.) A two-part video of the arrest can be found online. It is impressive mainly for the deluge of flattery that the handcuffed Ayers directs at the arresting officer as he is driven to the station. “I have a ton of respect for the state patrol,” Ayers tells him. At one point he asks brightly, “Can we chat politics?”

In 2006, Perdue was appointed chairman of the Republican Governors Association. Ayers became the RGA’s executive director—a spectacular promotion for a 24-year-old with no experience in national politics. Bennecke was the political director. Someone who met Ayers through the RGA remembers him dipping tobacco and partying frequently at the hotspots of D.C. in that era, places like Rhino Bar or Smith Point. For a time, he roomed with Bennecke. In 2005, Ayers had married Perdue’s second cousin, Jamie Floyd, although he would tell The Washington Post he was so consumed by his work that the couple “didn’t really have sex” for the first three years of their marriage.

“MY GOD, THEY ARE GOING TO GIVE HIM WHATEVER HE WANTS.”When Ayers showed up at the RGA, it was a bit of a backwater, mostly a place for parking spare corporate dollars. But it was about to transform into one of the most powerful loopholes in campaign finance law. Under the leadership of Mississippi governor Haley Barbour, who assumed the chairmanship in 2009, the organization took full advantage of its unique legal status. Unlike other major party committees, the RGA and its Democratic counterpart are not subject to regulation by the Federal Election Commission. The only oversight comes via a patchwork of state laws, which are often lax—and in many states, court rulings have made it nearly impossible to regulate the associations at all. This means the governors associations can solicit unlimited donations, unlike the party national committees. Although the RGA and DGA must disclose donors to the IRS, the list is essentially meaningless, since they don’t have to provide any information on where the money was spent or which races it was used to influence.

As it happened, Barbour took charge at the RGA just before the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision sanctioned unlimited corporate spending in elections, as long as that spending is “independent” of campaigns. Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, an election law expert and associate professor at Stetson University, argues that both the RGA and DGA are functioning as giant dark money operations. “They can basically funnel money to where there is the least enforcement of campaign finance law,” she said. “Pick your metaphor: daisy chains, Russian dolls, shell game …”

The 2010 midterms were set to be a huge year for the RGA—Republicans were fielding 37 gubernatorial candidates, including rising stars such as Nikki Haley and Scott Walker. And so Barbour created a club of the country’s wealthiest individual conservative donors, many of whom had been lackluster supporters of the RGA in the past. It was Ayers’ job to convince them that they could get a better return on their investment through the RGA than any other party machine. In this mission, he could not have had a better tutor than Barbour, whose fundraising prowess is legendary. “I think Nick would tell you he learned everything he knows from Haley,” said a former RGA colleague, Lauren Lofstrom. She recalled an evening in Chicago when Ayers charmed a clatch of billionaires, including Sam Zell and Ken Griffin, founder of Citadel. Some of the guests actually moved toward the edge of their seats as Ayers talked. “At the end I [thought,] ‘My God, they are going to give him whatever he asks for,’” Lofstrom said. According to Lofstrom, Griffin told Ayers that his talents were being wasted in politics and he should be working for his hedge fund. “Nick made people pause for the first time and go, maybe there’s more than just federal politics,” a former colleague said.

On Ayers’ watch, the RGA moved vast sums of donor money all around the country. When he joined the organization, its budget for the 2005-2006 election cycle was $43 million. By the end of the 2010 cycle, the budget had increased to $132 million. As for Ayers, he had amassed a Rolodex that would be the envy of his peers. Someone who knows him well said: “I’ve just watched: He can pick up the phone and call 30 governors, and they’ll all take his personal phone call. And he can pick up the phone and call the top 200 donors to give to governors in the country, and they’ll all take his phone call.”

In all, it was an experience totally unlike those of his contemporaries, who were working their way up on candidate campaigns or through other party organs with far greater restrictions on raising and spending money. Barbour told me that Ayers “matured beyond his age.”

When Ayers concluded his term in early 2011, he was being talked about as a successor to Karl Rove. He was expected to follow a well-trodden path: build up his own political consultancy, advise major candidates and help shape Republican politics. And so his friends were baffled when Ayers took a partnership at a media buying firm that was barely known in D.C. Target Enterprises was a company of about 15 people who worked out of an office tower in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley. Its founder, a brash New Yorker named David Bienstock, was about as far away as you could get from the Washington establishment. Ayers “was seen as a classy guy,” said a friend, explaining the consternation at his career move. “And Target wasn’t a classy compan

The sheer volume and speed of the transactions can obfuscate a lot of double-dealing. Campaigns are largely forced to trust that the media buyers pay the TV stations the contracted amount for the right ad spots. Two buyers emphasized to me that they pride themselves on returning leftover funds, suggesting that such scrupulousness may be the exception rather than the rule.

It is also not unusual, I was informed by a handful of industry insiders, for the consultant to privately negotiate a fee for bringing the media buyer the business. These sums can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars, far outstripping a consultant’s typical monthly retainer of around $15,000 on a gubernatorial or senate race. All of which provides a powerful incentive for the consultant to use the media buyer who will give him the best deal, not the one who will deliver the most effective ads. “That’s what happens a lot,” said one top buyer. Most political campaigns don’t conduct even perfunctory oversight of their spending. “There is no CFO on any campaign,” said the buyer. “There is a treasurer. The treasurer’s job is to make sure that the reports get filed properly at the FEC. That’s it.”

“IT’S MUCH EASIER FOR SOMEONE TO PULL THE WOOL OVER THE EYES OF A POLITICAL CLIENT THAN A CONSUMER CLIENT.”Until about a decade ago, Target Enterprises hardly had a presence in national political advertising. But in his West Coast milieu, David Bienstock was known as a consummate hustler. A flashy figure, he “was the kind of man to carry cash,” said a former colleague who remembers him being visited monthly at his offices by a banker who delivered envelopes of bills. Bienstock, who did not comment for this article, has a taste for lavish real estate. [3] His properties include a Sherman Oaks home previously owned by movie director Brian de Palma and a $5.6 million house in San Diego.He changes cars often and used to drive a gullwing model with doors that opened upward. The former colleague recalls a framed photo in Target’s hallway of Bienstock standing next to his favored private plane. He’s known as both a charmer and a screamer who sometimes holds court at Shutters on the Beach in Santa Monica, dressed in a black T-shirt and blue jeans. When discussing pitches with colleagues, he talks a lot about “the dangle”—that is, what the client really wants. He might say, “So, the dangle is … ”

In 2009, Bienstock acquired a right-hand man who could help him break into national politics. Adam Stoll, a former Goldman Sachs executive then in his mid-30s, had run New York governor George Pataki’s 2002 reelection campaign. Quiet and preppy, Stoll is Bienstock’s outward opposite. Someone who has worked with him remarked to me that “he probably showers in his suit.” Stoll was also a longtime friend of Ayers, who was then midway through his tenure at the RGA.

The RGA had never used Target before 2009. That year, the firm was hired to work on, among other things, the Virginia gubernatorial race—a “test run” of sorts, said someone involved with discussions between Ayers and Target. But Bienstock and Stoll wanted a much closer relationship with the RGA for 2010. So they invited Ayers and Bennecke to a retreat at the Wynn hotel in Las Vegas over the weekend of November 20 to cement a deal. The weekend “has become legend,” said one media consultant. “Nobody could figure out why Nick and Paul would even go anywhere with Bienstock. You’d see why if you met him … [he] makes my skin crawl.” One of the items on Saturday’s agenda was a talk by Bienstock: “Media Buying: The Inside Story … A View from Behind the Curtain.”

I talked to four people who have heard Target’s pitch. Their experiences were not identical, but two consultants gave very similar accounts of someone at Target proposing the following arrangement: Target would charge the campaign a much lower fee than its competitors. The Target representative would go on to explain that the company would later invoice for an amount that represented a payment for how much the firm had saved the campaign—with Target determining what the savings had been. This model might be described as “performance-based pay,” said an industry insider. A more accurate term, said one person who listened to the pitch, is “fucking bullshit.” However, most campaigns either lack the expertise to spot the catch in a highly technical pitch or are too focused on winning to closely monitor how their media budgets are spent. “It’s much easier for someone to pull the wool over the eyes of a political client than a consumer client,” said a veteran buyer in both spaces.

Whatever Target’s dangle to Ayers and Bennecke was, it seemed to be persuasive. “David can be very charismatic,” said the former colleague. In 2010, according to IRS filings, Target suddenly became the RGA’s biggest vendor, receiving $31 million for buying ads—about 36 percent of the RGA’s budget. (The next-highest-paid media buyer was Crossroads Media, which got $7 million.) Bennecke and Target did not respond to questions about Target, its business practices and its relationship with the RGA. I asked Haley Barbour why the RGA had chosen to give Target so much of its business. He told me he could “not recall that one firm got an especially large [share] of the media buy.”

I was curious to hear what Pawlenty thought of the fact that his campaign had paid nearly $600,000 for media buys through Target, according to FEC records. Ayers was not legally required to disclose his relationship with Target to the campaign, but various consultants I talked to argued that it would have been the ethically correct thing to do. Pawlenty paused. “That part I wasn’t as clear about,” he said, “as for what his status was relative to Target.”

After the campaign wound down, Ayers returned to Target and immediately resumed pitching the firm to his political friends. One recalled his firm receiving a classic Bienstock dangle: “I’ve got this great buying company. Doesn’t cost you anything.” This person actually ran a model using Target’s stated methodology and found that it would be more expensive than negotiating with the TV stations directly. And yet in the election cycle immediately following Ayers’ departure from the RGA, the organization gave Target at least 63 percent of its media business. [4]IRS filings show that the RGA paid Target more than $18 million in 2012 and a similar sum in 2014.

Ayers’s influence at the RGA was—and remains—significant. Ayers and his replacement, Phil Cox, were sufficiently close that Ayers would become an investor in Cox’s media business. The RGA’s general counsel, Michael Adams, would go on to work on personal legal matters for Ayers, according to a person who saw documentation. And many of Ayers’ team also stayed on after he left, according to a person who regularly deals with the RGA and remarked on their fierce loyalty to him. In 2014, when it came time for the RGA to select Cox’s successor, it named Ayers’ longtime friend, Paul Bennecke.

The RGA’s reliance on Target would become controversial among consultants—encouraging competition among vendors is what helps to keep prices down. (In response to questions, a spokesperson said the organization has been “managed with the utmost integrity.”)

“IT’S NOT LIKE STICKING YOUR HAND IN THE COOKIE JAR. IT’S AS IF HE BUILT A PENTHOUSE IN THE COOKIE JAR AND HAD EVERYBODY BRING HIM COOKIES.”And Target itself was attracting some scrutiny. Brian Baker is an attorney who runs a PAC affiliated with the Ricketts’ family, who are major conservative donors and the owners of the Chicago Cubs. Baker has told three people that in the spring of 2012, he had gone to some effort to check out Target’s practices. (Joe Ricketts intended to spend millions on Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign and Baker wanted to be sure he was dealing with an honest media buyer, two of the people said.) Based on the accounts of those three people, a clear story emerges. Baker visited a cable station in New England to follow up on some ad buys he’d asked Target to place. This was not a straightforward task. The FCC mandates that every TV station must maintain a public file recording purchased airtime for political ads, but many records are still kept in paper form. “It would have looked like a trash can,” said one of Baker’s confidantes.

According to the sources, Baker discovered a discrepancy between the services Target had promised to deliver and what actually ran on the air. Baker “hit the roof,” said one friend. Two of the sources recalled that he switched media buying firms.

When I asked Baker about this episode, he told me that “in no way, shape, or form, was there any irregularity.” He added, “When I began buying TV, radio and digital ads, Adam [Stoll]—a true pro—was a great help to me. While the groups I run work with a variety of media vendors, we have used Target since 2010 and continue to do to this day.” (Stoll and Target did not comment.) One of Baker’s confidantes told me, “You’re going to have a hard time getting people to screw with Pence and Nick Ayers.”

It was during this period that Ayers started aggressively working on races from multiple angles. He stayed on as a partner at Target, but also advised candidates and outside groups through his company, C5. In 2014, Ayers was working as the lead strategist for Bruce Rauner, the Chicago businessman who had launched a bid for governor of Illinois. Rauner’s campaign chose Target as its media firm. By the end of the race, the campaign had paid Target $15 million to make media buys, while C5 received more than $500,000 for its services.

These arrangements started to become conspicuously convoluted. In 2014, Target was working for David Perdue’s campaign for the U.S. Senate in Georgia. In that same race, C5 was retained by an outside group supporting Perdue (who is Ayers’ distant relation by marriage). Under federal election law, a campaign and outside groups can’t coordinate spending on any form of political communication, advertising included. To avoid allegations of coordination, vendors that work with both a campaign and outside groups typically create a firewall ensuring that no knowledge of the campaign’s “plans, projects, activities or needs” is shared. After reporters commented on Ayers’ role, he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that Target had instituted a firewall.

Both Rauner and Perdue won their races, which only served to burnish Ayers’ reputation as a Republican wunderkind. But despite all the business he was bringing to Target, Ayers never fully immersed himself in the company’s operations. “It was very hard to even get Nick on the phone,” someone who worked for the firm recalled. “If you needed him, you might not be able to find him for two days.” By early 2015, Ayers had left his partnership. Yet a relationship of sorts continued. On his White House disclosure form, which spans from 2015 to September 2017, he listed a “business partnership with Target.” And for every campaign he worked on after leaving the firm, Target served as a media buyer.

IN THE RUNUP TO THE 2016 ELECTION, Ayers was busier than ever. His most high-profile assignment was an attempt to rescue Indiana governor Mike Pence’s foundering reelection effort. [5] On March 29, 2015, Mike Pence gave an excruciating interview to ABC’s George Stephanopoulos. The Indiana governor repeatedly dodged the question of whether a new bill he’d just signed into law would enable discrimination against gay customers. As activists called for companies to avoid doing business in Indiana, Pence’s poll numbers plummeted.Ayers had pitched Pence on Target back in 2011. Pence didn’t use the firm, but had warmed to the young operative, not least because he was a fellow evangelical. “Ayers is very religious and Mike liked that about him,” said a Pence ally.

Ayers also spent 2016 talking up a new media arbitrage fund that would purchase TV advertising slots and resell them for a profit to campaigns of both parties, according to two sources pitched on the idea. He used his extensive Rolodex to enlist potential investors, including Texan oil and gas magnate Toby Neugebauer. After Trump won the nomination, Ayers acted as a part-time, unpaid adviser for the Trump campaign but kept pitching the arbitrage fund. “He assumed Trump was going to lose,” said someone he confided in at the time. “So he hedged himself.”

But perhaps his most ambitious venture was an effort to create his own political star—a candidate with the potential to one day go all the way to the White House. Eric Greitens, a candidate for governor of Missouri, was a GOP consultant’s dream. The 41-year-old was an intensely ambitious, chisel-jawed former Navy SEAL and Rhodes scholar turned best-selling author. [6] He reserved the domain name EricGreitensFor

President.com when he was only 34 years old.He had also been a lifelong Democrat until shortly before he entered the GOP primary. Greitens championed transparency in campaign finance. “We’ve already seen other candidates set up these secretive super PACs where they don’t take any responsibility for what they’re funding,” he said in a radio interview. “Because that’s how the game has always been played.”

After Ayers signed on as the campaign’s lead strategist in the summer of 2015, his influence quickly became visible. “Eric was a chalkboard, a very, very blank, black chalkboard. And Nick wrote in white chalk on the chalkboard whatever he wanted,” said a former member of the campaign who’d observed them together. Greitens replaced his campaign manager with a 20-year-old from Georgia named Austin Chambers. A Republican consultant described Chambers to me as Ayers’ “place holder.”

Under Chambers’ watch, the money flowed to some familiar names. Target was ultimately paid $21 million to buy media for the Greitens campaign. The digital team was replaced by a Target offshoot called BASK (the A stands for “Ayers”). And a C5 client called Something Else Strategies, a creative firm, was enlisted to produce ads, including one of Greitens firing a machine gun at “Obama’s Democrat machine.” Meanwhile, Ayers talked up Greitens at RGA meetings and introduced him around to donors. “We all thought Greitens was a golden boy,” the Pence ally told me. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, however, would question Greitens’ “oddly national” fundraising effort, which included sizable donations from people like Las Vegas casino mogul Sheldon Adelson and the now-disgraced Silicon Valley venture capitalist Michael Goguen: “Why would scores of business tycoons from Manhattan to Silicon Valley lavish contributions … on a political novice running in a primary election for governor of a Midwestern state where none of them live?”

Ayers would later give The Missouri Times an insight into the campaign’s strategy. It was important for Greitens not to peak early, he explained, or the other three contenders would have too much time to tear him down. As it happened, a dark money-funded super PAC would play a useful role. In the early summer of 2016, LG PAC started airing negative ads against two candidates in the GOP primary, seemingly on behalf of a third: Peter Kinder, the state’s sitting lieutenant governor, or LG. But LG PAC had nothing to do with Kinder. Near the end of the primary, it would emerge that the group was actually backing Greitens. It was an extremely clever ploy. By giving the impression that Kinder was the source of the attacks, LG PAC made Kinder look sleazy. [7] Kinder has said he did not purchase any negative advertising.It also allowed Greitens to maintain a lower profile, not to mention his image as a campaign finance crusader. Kinder told people the episode was the dirtiest political trick he’d witnessed in his career.

After the negative ads started airing, reporters unearthed video footage that captured Greitens talking with the LG PAC treasurer, Hank Monsees, at a May 19 campaign event. People started raising the possibility of illegal coordination. A photograph posted on Facebook showed Monsees on a phone in Greitens’ war room, apparently making calls for the campaign. (Monsees told The Associated Press that he was sitting down by the phones because he has a bad back. Asked why he had a phone to his ear in the photo, he said, “I may have played with the phones or something, but I made no calls.”) The chairman of the Missouri Democratic Party filed a complaint with the state ethics commission, which was dismissed. “The Ethics Commission is formed to be weak and able to do very little, and in this case they did very little,” said Scott Faughn, the publisher of The Missouri Times and a former politician. After Greitens won easily, the controversy over dark money died down. On January 9, 2017, he was sworn in with Ayers and Chambers at his side.

Almost a year later, however, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a government watchdog group, discovered a financial connection between LG PAC and Ayers. LG PAC’s sole funder was Freedom Frontier, a dark money nonprofit based outside Missouri that appears to have operated almost exclusively in the Greitens race that election cycle. On Ayers’ White House disclosure form, Freedom Frontier is listed as a client of C5 that he had personally worked for, during a very similar time frame. In national races governed by the Federal Election Commission, and in most states, it would be illegal for a campaign to coordinate with outside groups on ads. In Missouri, however, the laws on coordination are less explicit.

Freedom Frontier is no small-time advocacy outfit. It is part of an influential network of dark money groups that funnels donor money into elections nationwide and is clustered around an Ohio lawyer named David Langdon. The network, by design, defies easy explanation—there are nonprofits that fund PACs that fund campaigns, a constellation of blandly named entities linked by the same few legal representatives. But what is clear is that such groups have become an invaluable weapon in elections. They enable candidates to keep a respectable distance from negative ads, which voters dislike. In addition, nonprofits like Freedom Frontier—so-called 501(c)(4)s—are permitted to conceal the identity of donors. Their primary purpose is supposed to be issue-oriented, rather than political, but violations are hard to prove and rarely penalized.

Paul Ryan, the vice president of policy and litigation at Common Cause, a government accountability think tank, said that laws on both the state and federal level have not caught up with the explosion of dark money groups after Citizens United. Regulations on coordination, he said, are “wholly inadequate.” Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, the election law expert, added, “People using these opaque nonprofits are sort of making a calculated risk that no election regulator will stand in and stop them.”

Ayers’ ties to the Langdon network go back years. [8] In 2012, C5 was paid to raise funds for two nonprofits in the Langdon network: Citizens for a Working America (CWA) and the Government Integrity Fund (GIF). Between 2015 and 2016, C5 received $60,000 from a super PAC called Maryland USA, which paid Langdon’s law firm over the same period. Then, in 2016, a super PAC called SEALS for Truth donated nearly $2 million to the Greitens gubernatorial campaign, on which Ayers was the strategist. At the time this was a record-breaking donation in Missouri. The super PAC’s only funder was a nonprofit called American Policy Coalition, whose secretary is Langdon.It would be considered highly unusual for a consultant of his caliber to simultaneously work on a campaign and for a dark money group supporting that campaign. “One would think Ayers had enough business not to need income from both a campaign and the dark money group doing its independent expenditures,” said former Missouri state senator Jeff Smith, who has the dubious distinction of being perhaps the only person in the state to do prison time for coordination with an independent group. “Being paid by both entities certainly raises questions around coordination.”

The link between Ayers and Freedom Frontier is precisely the kind of association that is nearly impossible to detect in real time under current campaign finance laws. The only reason CREW was able to make the connection was because Ayers had to list C5’s clients on his White House financial disclosure—which chief investigator Matt Corley likened to “a light being shined in the dark.” And for once, this was a discovery that would not simply fade away.

Privately, however, he was less than thrilled with his situation. He had rare behind-the-scenes access to the president and vice president and wasn’t fully utilizing it. A big problem, as he saw it, was that he wasn’t getting paid. He called a political veteran asking if there was some kind of “special purpose vehicle,” such as a 501(c)(4) or PAC, that he could set up so he could at least be reimbursed (it was unclear by whom) for his trips to and from D.C.

After checking around with others, this person told Ayers that the proper way to cover those costs was to go through the RNC. Furthermore, this person added, Ayers could not advise the vice president—even voluntarily—while on a business trip paid for by private clients. Ayers, the political veteran recalled, seemed unsatisfied by the conversation.

Within weeks of this exchange, Pence launched a leadership PAC headed by Ayers and another Pence adviser, Marty Obst. A front-page New York Times article would later describe the PAC as the possible vehicle for a “shadow campaign” for the presidency, which would be unheard of so early in a new administration. (Pence called this claim “offensive.”) One of the PAC’s first large expenditures was $50,000 to C5. According to the most recent available records, C5 has received over $110,000 from the Great America Committee, including a payment as late as October. It occurred to the person whom Ayers had approached for advice that perhaps The New York Times had misread the point of the PAC. Ayers “was calling around about a [special purpose vehicle] and then weeks later suddenly there was the PAC. Oh my God: The PAC was the SPV for Ayers,” this person said. (Obst did not respond to a request for comment.)

These ethical questions only became more acute when Ayers finally entered the White House. Ordinarily, someone with a political consultancy would have been expected to divest himself of it to avoid the potential for conflicts of interest. For instance, when Karl Rove became George W. Bush’s senior adviser, he sold his political consulting business on the advice of Richard Painter, then the chief White House ethics lawyer. Rove also went on to sell his stock portfolio. While the sale was processing, he was prohibited from attending any meetings on energy because he owned Enron stock. Separately, Rove got a waiver allowing him to talk to former clients if, for example, there was a government investigation or regulation that directly involved them. By selling his business, Rove had removed the prospect of those conversations being motivated by personal gain.

In contrast, by retaining his business, Ayers created a situation where even the most mundane matters could create the appearance of an improper conflict. Under 18 U.S.C. 208 it is illegal for a government employee to participate in any matters in his official position that could have a direct or predictable effect on his business. A chief of staff to the vice president can be called upon to help make all kinds of decisions that would have implications for a consulting firm looking for work—whom to endorse, whom to welcome into the White House, where to campaign, which event to show up for. “I think it’s a very dangerous situation,” Painter said. “It’s hard to avoid doing something in your official capacity that’s not going to affect [the consultancy].”

To give one example of the resulting murkiness: Earlier this year, Pence had a photo taken in his office with Tom Campbell, a farmer running for Congress in North Dakota in the 2018 midterms. It was a seemingly routine photo op. And yet around that time, Campbell was receiving media advice from Something Else Strategies, a client of C5. [10] According to Ayers’ White House disclosure, Something Else Strategies has paid C5 for “consulting services.”(A Something Else partner, Heath Thompson, has also had his picture taken with Pence and Ayers.) Campbell touted the photo with Pence on social media. Situations like these could create an incentive for companies to work with C5 if they think Ayers might connect them or their clients with Pence—whether or not Ayers has any idea of the client’s intentions. (Something Else Strategies did not respond to questions.)

For someone in Ayers’ job, it’s nearly impossible to take precautions that avoid the appearance of an illegal or improper conflict. According to ethics experts, there are really only two options: Recuse yourself from any government work that could affect your business, or divest from it. The first option is extremely impractical for someone with Ayers’ responsibilities. “How can he possibly recuse himself from every issue that affects his clients given who his clients are? That’s why you don’t see any lobbyists, lawyers or PR people enter the White House and keep their private practice,” said a former senior White House official who divested from his business. Richard Painter endorsed this view. “If I had had anyone say they want to own a political consultancy firm … while they’re working in the White House,” he told me, “I’d say you’re out of here.”

Then there is Ayers’ role for the Pence leadership PAC, which has given out over $200,000 to candidates so far. Since this work is in a private capacity, 18 U.S.C. 208 does not apply. However, any move Ayers made to direct donor dollars into a race that C5 was working on could arguably affect the company’s bottom line. As a top-tier political consultant put it, “It’s not like sticking your hand in the cookie jar. It’s as if he built a penthouse in the cookie jar and had everybody bring him cookies.”

Painter told me that Ayers’ prevarication over selling C5 was so unorthodox that it is difficult to untangle the threads. “What you have here is new,” Painter said. “It’s the same nonsense we’re hearing from Donald Trump because he turned the business over to his son. Now everybody else wants to play the same game.”

I had been trying to find out when Ayers planned to sell C5 since October 2017, when it was reported that he had been issued a sweeping waiver allowing him to talk to C5 clients. I had heard he had plans to sell by the end of the year. That did not happen. The company is a Georgia corporation, and on January 23 of this year, it was registered to do business in Virginia, where the Ayers family moved last year. His wife, Jamie, was recorded as the “registered agent.” The company’s Georgia paperwork previously named Nick Ayers as its CEO, chief financial officer and secretary. But in an annual filing dated February 3, Jamie Ayers was listed in those roles.

One person who knows Jamie Ayers described her as “one of the nicest, sweetest Southern belles you’ve ever met” and “no more capable of running a political consulting firm than the man in the moon.” Meanwhile, Austin Chambers, the operative perceived to be Ayers’ acolyte on the Greitens campaign, appears to be working for C5 and is using a company email address. He did not respond to a request for comment. C5 has already been paid this year by the reelection campaign of Alabama governor Kay Ivey.

In late February, I went back to Pence’s office for clarification about Ayers’ ownership of C5. A couple of weeks later, after repeated requests, I received an emailed statement from Alyssa Farah, Pence’s press secretary. The statement is notable for its elaborate use of tenses: “As Nick Ayers’ May financial disclosure will reflect, he sold and relinquished one hundred percent of his ownership of C5 including all stock, ownership interest, and managerial control. Additionally, no member of his family nor existing or former employee will have any control, or interest in it. This was all overseen and completed by White House ethics’ rules and within their timeline.”

Farah did not provide the date of the sale or any supporting documentation in response to multiple follow-up questions. The statement “suggests he may not have sold his business yet,” said Larry Noble, general counsel for the Campaign Legal Center. “He should be able to show proof that he divested himself from the business. … A carefully worded statement by a press secretary about what he will do in the future does not resolve any of the issues.’’

IN JANUARY, Eric Greitens’ political future exploded when a local news station reported allegations that he had tied a woman to gym equipment in the basement of his home, blindfolded her, taken a picture and then used it as blackmail. Greitens admitted to an extramarital affair, but denied blackmailing the woman, who had been his hairdresser. On February 22, he was indicted by a grand jury on a felony invasion of privacy charge.

A criminal investigation by the St. Louis Circuit Attorney’s Office is underway, as is a separate inquiry by the Missouri House of Representatives. According to CNN, the FBI is also looking into Greitens. Some of these inquiries may be expanding beyond the blackmail allegation. State lawmakers have said that the Circuit Attorney may be looking into donations to A New Missouri, a nonprofit that promotes the Greitens agenda. Ayers has advised A New Missouri, according to his disclosure form. One person who has been interviewed by federal investigators told me that both A New Missouri and LG PAC came up during the conversation.

A Republican operative close to Pence insisted that the vice president isn’t naïve about Ayers: “He is fully aware of Nick’s strengths and his weaknesses.” Still, Pence has not comprehended “the full extent” of Ayers’ business activities, this person said. Over Christmas, Pence visited the Aspen home of Toby Neugebauer. The Texas businessman told Pence that in his view, Ayers would have a higher market value in the private sector than any other member of the administration except Gary Cohn (who has since announced his resignation). The vice president, Neugebauer said, was impressed—and pleased to think that such a person was helping to lead his team. However, the Republican operative is convinced that Pence has no idea of Ayers’ ties to the dark money groups in the Greitens race and the surrounding controversy.

In recent months, a friend of Trump had lunch with the president at the White House. Over the course of the meal, Pence kept popping in and trying to interrupt. By the visitor’s account, it seemed as if Pence was trying to figure out what they might be talking about. As it happened, the lunch guest wanted to talk to Trump about Ayers, among other things. It seemed to him that Pence was a loyal vice president but that his chief of staff had his own agenda. He decided to sound a warning note with a reference to Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” “Yon Nick Ayers has a lean and hungry look,” he told the president. Trump did not reply.