On a bright St. Petersburg evening this past spring, as the pale Russian sun glittered on the Neva River, Mikhael Piotrovsky, the director of the State Hermitage Museum, stood up at a dinner attended by curators and art critics at Menshikov Palace. Raising his glass, Piotrovsky asked the guests—many of whom had own around the globe to be at the dinner—to toast the most expensive art show in history, a blockbuster among blockbusters headed from Russia to the West.

The artworks—130 Impressionist and Modernist masterpieces, including some of the greatest works ever created by artists such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh—are stupefying to behold. Billed almost too modestly as “Icons of Modern Art,” the show pays tribute to a private collection so magisterial it occupies entire wings at two separate museums, the Hermitage and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

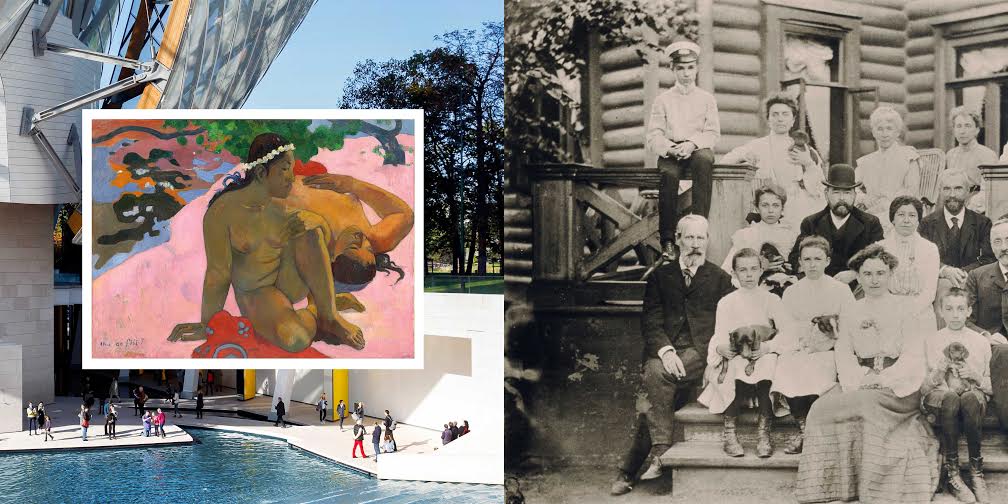

When the four-month-long exhibition opens on October 22 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, the private art museum and cultural center designed by Frank Gehry, major heads of state are likely to attend, not least the presidents of Russia and France. Among other draws: the chance to see cornerstones of Western culture, including many of Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings and Matisse’s The Dance (arguably his most recognizable work), that have spent much of their existence out of sight to the West.

“This is is a historic event that will have people coming from all over the world, something we are not likely to see again for a while,” says Jean-Paul Claverie, an adviser to Bernard Arnault, the richest man in France and the chairman and CEO of the multinational luxury conglomerate LVMH, which is financing the show.

“I can’t stress how in infrequently we see a show of this magnitude,” says Evan Beard, national art services executive for U.S. Trust and an adviser to many private collectors. He calls the collection “so staggeringly valuable that it’s almost hard to conceive.” But what may be even more astonishing is the story behind it, a tale of incomprehensible loss and redemption visited upon perhaps the greatest art collector the world has ever known.

That figure is Sergei Shchukin, a Moscow textile magnate who in 1890 began visiting the salons of Paris, where he developed a taste for Impressionist art. One of Russia’s richest men (but not a member of its old-guard aristocracy), Shchukin bought Lilac of Argenteuil, his first of 13 paintings by Claude Monet, just before his 44th birthday. Over the next few years he would add major works by Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, and van Gogh, which represented a decadent avant-garde to turn-of-the-century Moscow—a city undergoing headlong industrialization, with the simultaneous rise of a new moneyed elite.

What the paintings really represented, according to Shchukin’s grandson André-Marc Delocque-Fourcaud, the 74-year-old former director of various museums in France, was “the taste of wealthy bourgeoisie: nice, trendy, not revolutionary.” As a prominent businessman—the sort of figure who today would own a hedge fund and purchase art at Gagosian—Shchukin bought art to impress other businessmen and “show you are a big man,” says Delocque-Fourcaud.

“Shchukin was a prominent businessman—the sort of figure who today would own a hedge fund and purchase art at Gagosioan.”

“There was a strange, artificial, hothouse atmosphere in Russia at the turn of the century, a sense of forced growth and impending metamorphosis,” writes Shchukin’s biographer, Beverly Whitney Kean. “It was a single leap from feudalism to the industrialism of the 20th century, and the process was jarring, unsettling the traditions of centuries of isolation and undermining a rigidly stratified social structure.” In this setting a “collector’s fever” began to grip the new moneyed class.

Soon after buying his first paintings, the handsome, urbane Shchukin—whose creation of an international textile empire had depended on his visual acuity—was introduced to the arrestingly exotic works of Gauguin, “as alien as moon rocks,” according to Kean. At the time, not only conservative Russians but the art establishment in Europe failed to appreciate Gauguin’s vivid Fauvist style, but Shchukin, who was known in the business world for shrewdness and daring, saw something (“If a picture gives you a psychological shock, buy it,” he would later say), and his method of collecting began to change. Instead of pursuing art for status or prestige (or financial incentives, as so many collectors do today), Shchukin—who belonged to a puritanical sect of the Russian Orthodox church and led an ascetic lifestyle—viewed collecting as a challenge from God.

“You have been given the eye,” Delocque-Fourcaud explains to me. Tragically, the grandson adds, “there is a price for that.”

In Moscow, 1905 was a year of riots and bombings, a harbinger of the Russian Revolution, and in November the youngest of Shchukin’s three sons simply disappeared. Months later, during the spring thaw, his body was found in the Moscow River, where he had thrown himself, upending the family. Shchukin’s self-therapy for his grief was to change the history of Western culture.

A month after the burial he sought out the 36-year-old poverty-stricken Henri Matisse at his fifth-floor studio on Quai St.-Michel. Ridiculed by the French art establishment as a charlatan, Matisse was in a critical early stage of experimentation. Shchukin bought a still life, Crockery on a Table, and sent it back to Moscow, where he boldly put it on display, inviting mockery or worse. (Viewers had been known to deface Matisse’s work.)

In 1906, Shchukin began hurriedly buying Gauguin, eventually sending 16 of the Primitivist’s most iconic paintings to his mansion in Moscow. Delocque-Fourcaud has no doubt that the suddenly manic collector was building a monument to his dead son, who was thought to have killed himself in despair over Russia’s social turmoil.

More sorrow was to come. On Christmas Eve 1906, Shchukin’s wife Lidya, who was known as one of Moscow’s great beauties, returned from a shopping spree feeling unwell. A week later she was dead of what was termed “a woman’s disease,” according to biographer Kean. Shchukin, says his grandson, rushed out into the subzero Moscow night and knocked on the door of Valentin Serov, Russia’s most acclaimed portraitist, and asked him to paint Lidya in death. Soon Shchukin left Russia and embarked on a pilgrimage to the Monastery of St. Catherine at the base of Mount Sinai.

Traversing the Egyptian desert in a caravan of 20 camels, plagued by insects, heat, and guilt, he found himself transfixed by, as he wrote, “the blue mountains, the sea, the rising of the sun and the sunset” on the Gulf of Aqaba—and, one day, in a revelation, the vivid, colorful paintings of a young monk working in a style similar to that of Matisse. He rushed home to immerse himself in color and art.

On his return to Moscow he received a telegram announcing that his brother Ivan, a profligate socialite living o family funds in Paris, had killed himself. Sergei had cut him off , and Ivan had tried to sell his own art collection, only to be told that many of the works were fake. (In yet another tragic twist, they would turn out to be authentic.) Shchukin sought out Matisse again, commissioning a panel of a woman eating fruit from a bowl, hoping it would brighten the Russian winter like a blast of light. But when, months later, the painting arrived in Moscow, it was the wrong color—Shchukin had requested that the scene be painted in blue, but Matisse had used crimson (creating his beloved Harmony in Red). Unflinchingly, Shchukin wrote the artist that the change pleased him “enormously” and subsequently became his patron, supporting him at the most critical point of his career.

“He wanted art that was a knock in the face,” says Delocque-Fourcaud, and he wanted others to feel it too. us, at considerable risk, he began opening his Moscow home, the magnificent Trubetskoy

Palace, to the public. When a year later he unveiled The Dance and Music, mammoth works now considered Matisse’s greatest masterpieces, there was an uproar. Some thought Shchukin had gone mad, but after debating with the artist whether to halt the commission, he wrote to Matisse, “Allons-y”: Let’s do it.

Matisse repaid his sponsor by introducing him to an up-and-coming Spanish artist, Pablo Picasso, whose darkness initially repelled Shchukin. But the collector soon came around, buying Woman with a Fan, the first of 50 Picassos he would eventually own.

Yet more tragedy was to come. In 1911, on the third anniversary of Lidya’s death, another son killed himself, intensifying Shchukin’s belief that art was the quid pro quo for his suffering.

Shchukin’s ultimate collection is today estimated at $10 billion, making him on paper the most successful collector of all time.

If so, the rewards were handsome. Shchukin’s ultimate collection—256 pieces bought between 1888 and 1917—is today estimated to be worth $10 billion, making him on paper the most successful collector of all time. In all likelihood, however, what was more important to Shchukin was his influence on art history.

“He built the collection during a great inflection point in the history of the art market,” says Evan Beard of U.S. Trust. “During this time, art market control shifted from state-sanctioned institutions like the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris to an independent dealer model. Artists went from being high-end civil servants to avant-garde capitalists like Picasso who realized that lasting in influence came by changing the conversation.

Gallerists like Ambroise Vollard and Paul Durand-Ruel—the Leo Castelli and David Zwirner of the day—targeted a guy like Shchukin, who wanted art as a way to elevate his social status and had the money to do it. It was the beginning of the capitalist art market we know now.”

“Shchukin and a handful of other collectors were far more important in shaping and elevating art than the collectors of today,” says art historian Olivier Berggruen. “Contemporary art is not scandalous in the way the avant-garde was. Shchukin was a great collector of the avant-garde at a moment when the avant- garde was shunned by the establishment.”

“When one goes to Russia,” says Edward Dolman, chairman and CEO of the Phillips auction house, “and sees all those master- pieces lined up on a wall, one is reminded that the heart of so much European culture is actually Russian.”

The Revolution came in 1917, and Shchukin fled to Germany then Switzerland, and finally Paris, where he remained. Unlike many of his piers, who were reduced to poverty, he succeeded in moving assets abroad (including diamonds stuffed in a doll) and maintaining a comfortable lifestyle. He still collected art, buying gloomy works by Raoul Dufy and Henri Le Fauconnier that “reflected a mood of exile,” according to Delocque-Fourcaud (whose mother Irina was the daughter of Shchukin’s second wife, a concert pianist he had married before fleeing Russia). However, he lived quietly and avoided Matisse and Picasso, perhaps out of pride.

His collection stayed behind, inside Trubetskoy Palace, which was renamed the State Museum for Modern Western Art, and held up as an example of “crazy bourgeois tastes,” says Alexey Petukhov, curator of 19th- and 20th-century European and American art at the Pushkin Museum. A sensation, the museum attracted cultural pilgrims from everywhere until the onset of World War II, during which the art was crated and sent east, beyond the Urals. The world’s greatest collection of European modern art was soon no longer welcome, its contents viewed as “cosmopolitan” and dangerously un-socialist. Stalin ordered that the collection be broken up, supposedly threatening to “hang the man who hangs Picasso.”

Thanks, however, to the Hermitage—the wife of the director at the time was a modern art lover—the pieces seen as the most degenerate were rescued, and they ended up in the vast St. Petersburg museum, consigned to the basement with a promise never to be shown. The Impressionist works, meanwhile, were at the Pushkin, also buried in storage. Not until the Khrushchev era were the paintings exhibited—in the case of the Pushkin, in a “small, inaccessible back room,” according to Kean, who was baffled to find the name Sergei Shchukin (who had died in Paris in 1936 at the age of 82) erased from Soviet history.

Some pieces were allowed to travel abroad. In 1970, for the centennial of Matisse’s birth, The Dance and Music (the latter will not be included in the upcoming exhibit because of its poor condition) were shown in Paris for the first time in 60 years, at the Grand Palais. However, their provenance was mysteriously attributed to “a private collection,” outraging Shchukin’s descendants, who threatened to sue any government that borrowed paintings from it, effectively confining the collection to Russia, divided and divorced from its own history, in “complete oblivion of the man…who sacrificed so much, including his own children,” Delocque-Fourcaud says.

The Russian art community knew the story behind the collection and would occasionally reach out to Shchukin’s descendants in the hope of a reconciliation. In 2012, while visiting the Hermitage, Delocque-Fourcaud relented in his legal threats and agreed to support an exhibition in France if it properly highlighted his grandfather’s legacy, not just the individual artworks. But then the real obstacle to showcasing the Shchukin collection reared its head.

Every museum today lives in fear of having prize pieces taken away in lawsuits by people, institutions, or whole countries claiming to be the rightful owners. Both the Pushkin and the Hermitage worried that the other museum, each representing the city claiming to be the true home of the Russian soul, would use a show abroad as an excuse to seize what has become, since the 1980s, hugely popular attractions. (The Shchukin collection at the Hermitage, which includes Matisse’s The Dance and Monet’s Lady in the Garden, occupies more than a dozen rooms.)

The dispute reached the boiling point and became international news in 2012, when the Pushkin’s formidable 91-year-old director, Irina Antonova, confronted Vladimir Putin on live television, challenging him to “redress the injustices of the past against the citizens” and unite the collections—in Moscow, of course. Thanks to the spectacle it caused, the move cost Antonova her job. Her less truculent replacement, Marina Loshak, publicly dropped efforts to permanently reunite the collection, enabling the Paris exhibition to advance. However, Loshak told me she has not given up hope of uniting “a lot” of the collection, if only temporarily, at the Trubetskoy Palace.

With the Russians not at each other’s throats, Delocque-Fourcaud cannily reached out to Anne Baldassari, the eminent former director of Paris’s Picasso Museum. Baldassari was herself a subject of controversy, having been terminated over an alleged dispute with the Picasso family. Now free to tackle the Shchukin dilemma, she told him that exhibiting the entire collection was a “dream—there are more people who dream that than you think. But the problem is the cost. No national museum has the capacity to afford the insurance and transport of pictures of that quality.”

Only the Fondation Louis Vuitton would have the means. Moreover, she argued, the Fondation’s extravagant, Frank Gehry–designed building, which had recently opened, “needed content” to match the soaring architecture. As it happened, Delocque-Fourcaud had once worked with Jean-Paul Claverie— known as Bernard Arnault’s right-hand man—and was able to get an immediate answer from the art-loving mogul: “Allons-y.” LVMH would pay to finally reunite the collection—65 pieces from each museum, including all but a few too-delicate-to-travel masterworks, such as Music—in, as Baldassari put it, the “radically contemporary space” of the Fondation.

” ‘Icons of Modern Art’ will be a historic event,” Claverie later said, emphasizing that Arnault (who declined to comment) intends “to pay tribute to the vision and passion of an extraordinary collector and to highlight the role patrons often play in bringing together the collections of our most important public institutions.” After February the art will return to Russia.

Of course, the parallels between Arnault, who grew a family business into a global powerhouse and later in life became a passionate collector, and Shchukin are not lost on Delocque-Fourcaud. “You are the continuation of Shchukin,” the grandson told Arnault when the two met. Arnault shook his head: “Not yet. It’s too soon to know.”

In Moscow I attempted to visit the Trubetskoy Palace, which was given to the Soviet Department of Defense under Stalin. It looked strangely peaceful on a May afternoon, with sunlight bouncing off the exterior walls. A mysterious mythology still lingers about the building, at least in Moscow. “If you take a photograph you will be arrested,” my companion, a curator at the Pushkin, warned me. Too late—I had already taken one.

Russians may have a different relationship with power and wealth, it occurred to me. They accept the fleeting nature of these things, which is why, perhaps, men like Sergei Shchukin consume so much so fast. They sense how quickly it can disappear. Mikhael Piotrovsky’s opening dinner for the Shchukin show had been held at a branch of the Hermitage, the Menshikov Palace, the grand former home of one Alexander Menshikov, who had risen from humble origins to become a friend of Peter the Great. The palace was considered the nest in St. Petersburg, but Menshikov overreached in trying to marry his daughter to Peter’s grandson, and, just as quickly as he had risen, he was stripped of his palace and the stupendous wealth he had accumulated and exiled to Siberia. at one man could amass and lose so much in one lifetime was astonishing, but when I expressed surprise my guide just shrugged.

“Welcome,” he said, “to Russia.”